7 Ways to Manage Large-Scale Taxonomies

Published on Jan 29, 2026, filed under development, maintainability. (Share this post, e.g. on Mastodon or on Bluesky.)

Before we begin, I’m not a taxonomy expert and likely use the term liberally. So if you’re an expert who sees me do nonsense, please correct me—thanks!

Frontend Dogma is a web development news site and archive with tens of thousands of entries and more than a thousand tags.

Although “large-scale” taxonomies might be much larger than that, working on an open, growing, long-term project like this comes with challenges. Here are some of the things I do in order to feel like I have Frontend Dogma’s taxonomy under control—and I say that as someone who appreciates order.

Contents

- Define Tagging Rules

- Introduce a Minimum Number of Entries per Tag

- Make It Easy to Use Existing Tags

- Define and Show Tag Relationships

- Make It Possible to Combine Tags

- Consider Placeholder Tags

- Regularly Review and Update Tags

- Bonus: Chart a Tag Tree

1. Define Tagging Rules

What determines what tags are being used?

On Frontend Dogma, I found that this depends on what the material is (like a video or interview), what it’s about (topics explicitly mentioned), but also what the material contains (e.g., examples or link lists).

This is useful to be clear about and write down.

2. Introduce a Minimum Number of Entries per Tag

On a small site, tagging spontaneously works. On a large site, it leads to uncontrolled tag growth.

I’m working with a minimum of 3 entries (preferably 4–5) that fit a particular tag before I use that tag. (Until that’s the case, tag candidates are commented. A supplemental script helps me identify “ripe” and “overripe” tags.)

This comes not only with the benefit of being intentional about tags and therefore preventing accelerated tag growth, but it’s also more useful for users—any tag features at least some material.

3. Make It Easy to Use Existing Tags

In order to make it easier to use tags, and to use the same tags, it’s important to expose tags and make them selectable.

Many systems (e.g., WordPress) come with this option. For Frontend Dogma, I feature all tags in the intake tool I wrote specifically for the site; what’s more, the tool also adds tags that are usually connected with others (e.g., “chrome” would also automatically be tagged “browsers” and “google”).

4. Define and Show Tag Relationships

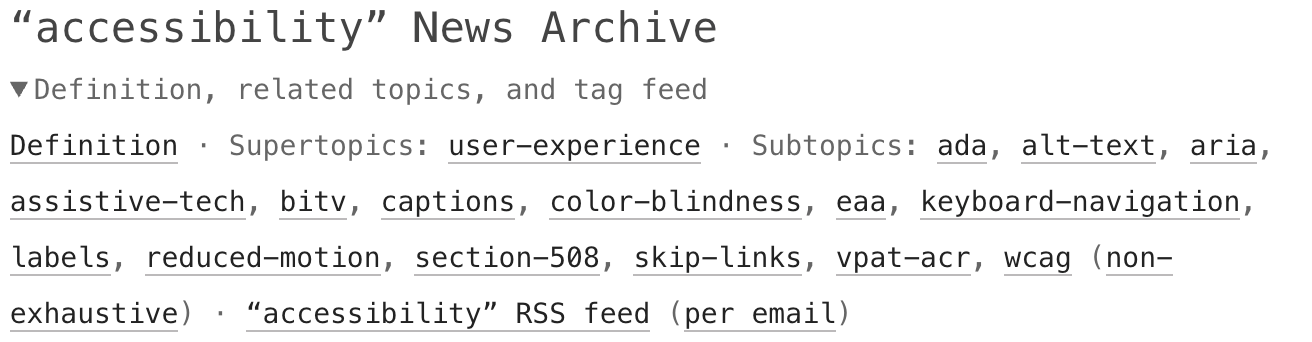

Still, with many and an increasing number of tags, it’s easy to miss certain tags. To counter that, I’ve found it useful to establish a connection between tags even if it isn’t made explicit by the tags themselves.

Establishing and calling out tag relationships serve as a safety net to still allow to find related information.

5. Make It Possible to Combine Tags

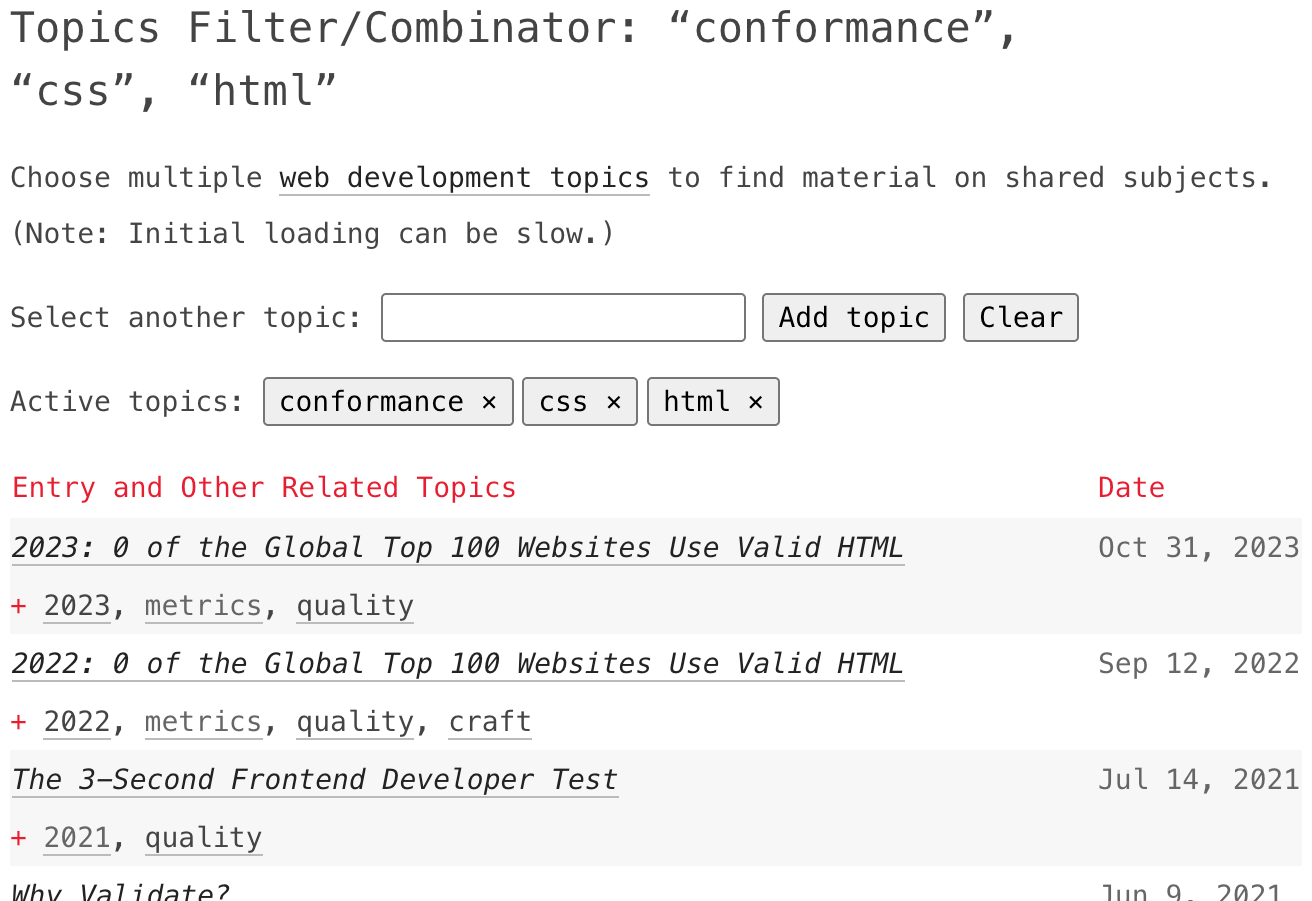

Especially in large taxonomies, tags can be a lot more powerful when it’s possible to combine them. This way, tags can be explored in depth.

On Frontend Dogma, I decided to provide an array of all articles and tags that can be queried on a special “filter/combinator” page:

This comes with some trade-offs—e.g., build a simple heavy solution or a complex fast solution—, but adds a lot of value in a tag-rich environment.

6. Consider Placeholder Tags

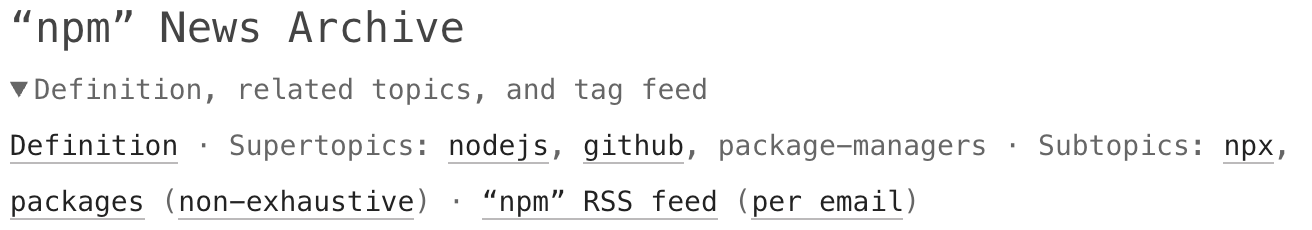

For tags that are so obviously related that they don’t add value, unlinked placeholder tags can complement tag relationships to provide context without constituting a tag.

On Frontend Dogma, for example, there’s coverage on many different languages (tag all of them “programming languages”?), but also different types of tools (“package managers”?). Adding tags for everything doesn’t make sense and needs to be guarded against.

So what to do? I like to work with unlinked tags to stand in for a possible future tag, something that gives extra context without letting the architecture swell:

These placeholders are part of a tag map file that structures all tags on Frontend Dogma.

7. Regularly Review and Update Tags

As with anything that is intended to last, tags and taxonomies need maintenance. This includes regularly reviewing and updating tags.

In case of Frontend Dogma, two things help with that:

Old-fashioned reminders ensure reviews are being done in the first place.

Then, home-made, AI-generated scripts (like the supplemental script mentioned above) help identify tags with few uses, as well as any (commented and therefore unpublished ones) that may be numerous enough to be enabled.

Bonus: Chart a Tag Tree

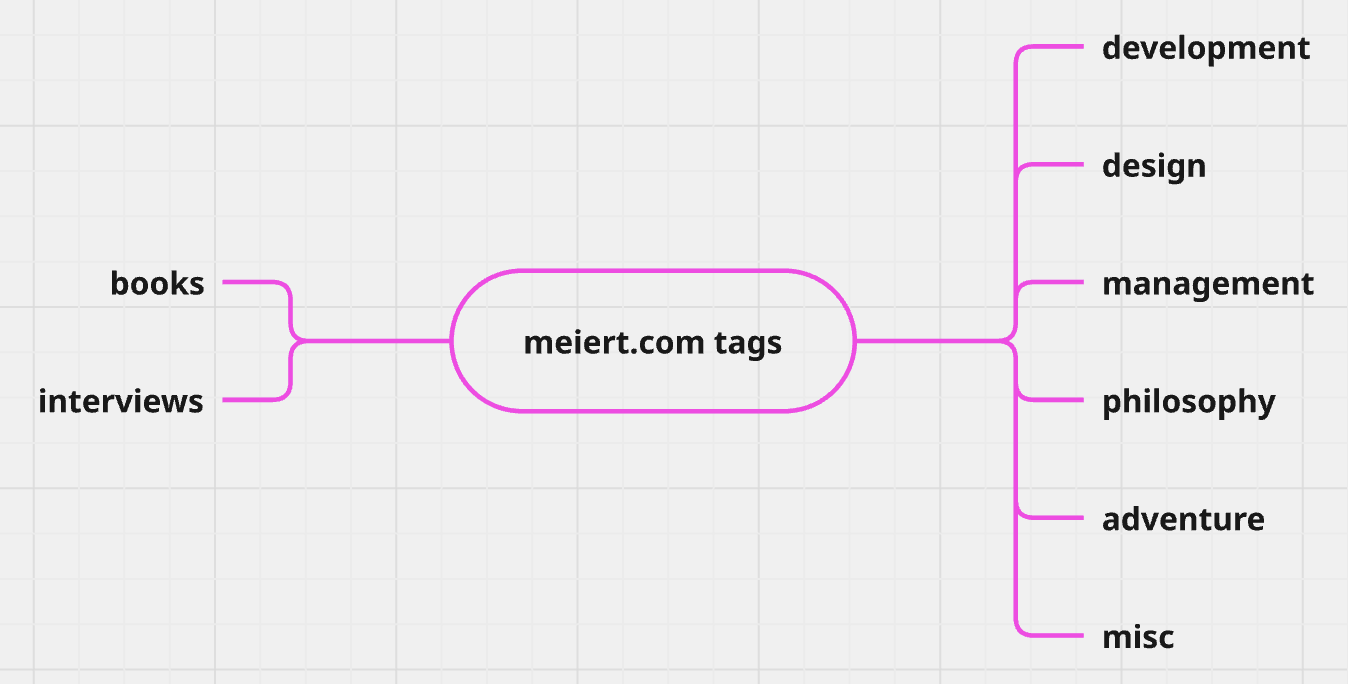

With smaller taxonomies that work with “primary” (mandatory) and “secondary” (optional) tags, here’s another potential tool: a tag tree (also fine: mind map). Here’s a sample from the one I use on meiert.com:

This goes back to being clear about the tags to use, and is useful because it gives some visual indication of the respective system.

_ This is certainly not “it,” and I’m submitting these as observations I’ve made to have a sense of control over tag collections as large as Frontend Dogma’s.

If you’re successfully managing something similar or larger, what works well for you? Please share as a response to the announcement of this post on Mastodon, Bluesky, or LinkedIn!

About Me

I’m Jens (long: Jens Oliver Meiert), and I’m an engineering lead, guerrilla philosopher, and indie publisher. I’ve worked as a technical lead and engineering manager for companies you use every day (like Google) and companies you’ve never heard of, I’m an occasional contributor to web standards (like HTML, CSS, WCAG), and I write and review books for O’Reilly and Frontend Dogma.

I love trying things, not only in web development and engineering management, but also with respect to politics and philosophy. Here on meiert.com I talk about some of my experiences and perspectives. (Please share feedback: Interpret charitably, but do be critical.)