Not Knowable

Published on Sep 29, 2024, filed under philosophy. (Share this post, e.g. on Mastodon or on Bluesky.)

Are you familiar with the “proof by ignorance”? Quoting Gary Lorrison (Analytical Thinking):

[The proof by ignorance] is the mistaken supposition that, if there is no evidence for the existence of something, then it doesn’t exist.

What I find interesting is that, sure, for all practical purposes, there are things for which we have no evidence (that is, which we don’t know), and that do, of course, exist.

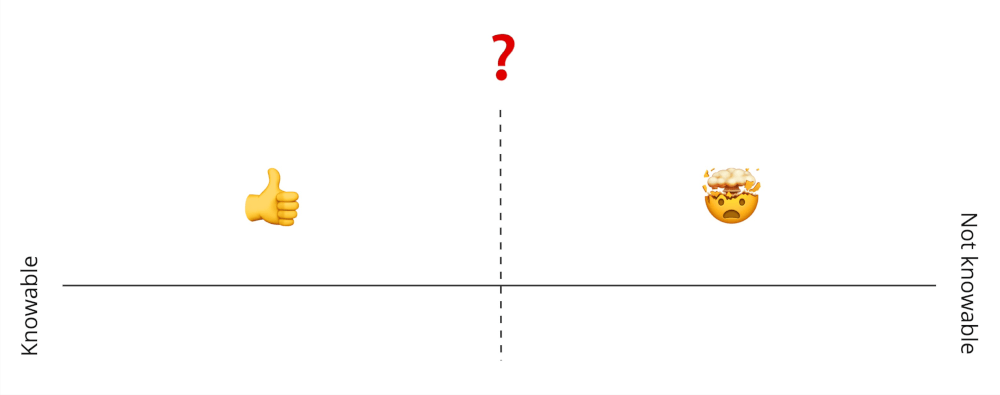

I also find interesting that we don’t know how much we don’t know. (If you look at the beautiful graphic below, the dashed line must probably run more to the left than to the right, which makes this even more fascinating!)

I find interesting how much of what we don’t know may be unknowable. (For a heavyweight example, it would make a lot of sense for us not to be able to remember past lives, given that only that would offer a fully immersive experience in the current life.)

And I find interesting how we have absolutely no way of dealing with what we don’t know—and what is not knowable.

On that last note, we probably do—but that way of dealing with what we don’t know seems to be based on imagination, intuition, and faith, something we may be so removed from that… effectively, we have no way of dealing with what we don’t know. Which I find interesting both from an individual and collective point of view.

Finally, what I find most interesting, is that we may, indeed, know it all—as part of the Absolute, of “All That Is,” encountering the Divine Dichotomy. But we choose not to.

Not now.

Not knowable.

I tend to be pretty casual in philosophical posts like this one. That leads to problems ranging from not providing enough context (what are the premises), not arguing concisely enough, and not backing up statements enough. It also comes with the problem of forming a habit. I’m aware of these issues, but am accepting them in order to move fast. That said, always share constructively critical feedback.

About Me

I’m Jens (long: Jens Oliver Meiert), and I’m a senior engineering lead, guerrilla philosopher, and indie publisher. I’ve worked as a technical lead and engineering manager for companies you use every day and companies you’ve never heard of, I’m an occasional contributor to web standards (like HTML, CSS, WCAG), and I write and review books for O’Reilly and Frontend Dogma.

I love trying things, not only in web development and engineering management, but also in philosophy. Here on meiert.com I share some of my experiences and perspectives. (I value you being critical, interpreting charitably, and giving feedback.)