Requirements for Website Prototypes (and Design Systems)

Published on Jun 9, 2007 (updated Feb 5, 2024), filed under design, development (feed). (Share this on Mastodon or Bluesky?)

This and many other posts are also available as a pretty, well-behaved ebook: On Web Development.

The following article provides the outline of the talk I intended to hold at the webinale 07 in Ludwigsburg. It covers best practices for website prototypes based on HTML, CSS, and DOM scripting.

Contents

Definitions

- Prototype:

- A project-related collection of static or dynamic templates made of HTML, CSS, and DOM scripting.

- A microcosm of your online investment.

Accordingly, factors like technical foundation, information architecture, or quality assurance—for example, through automated tests—are not covered here since the principles below have to be viewed independently.

Problem

Bad (and, even more so, non-existent) prototypes cost money.

Requirements

Universality

Include everything that is used live.

The “What,” meaning page types and elements.

Actuality

Include everything that is used live.

The “How,” meaning any other changes to the live website.

Realism

- Make use of realistic keywords and realistic microcontent.

- Address different use cases.

But: Dummy text is okay.

The use of realistic microcontent more likely means consideration of conceptual aspects as well as a lower risk of “implementation losses.” Different use cases serve visual integrity—do certain teaser constellations work, does the leading of long list entries read well, and so on.

Focus

Keep it simple, avoid redundancies.

The goal: A prototype must not become the live website.

Accessibility

Take into account a broad audience:

- developers (for developing and testing),

- project managers (for inspection from the inside),

- clients (for inspection from the outside),

- users (for usability tests).

While web and software developers always belong to the audience of prototypes, other groups are often ignored. This is wasted potential—and wasted money. Furthermore, the “users” group means a change in requirements since it requires more realism and less focus.

Availability

Offer a stable URL in order to:

- enable continuous use,

- emphasize the importance of the prototype.

…which isn’t possible with local and temporary prototype installations.

Commitment

- Requirements and changes in the prototype induce changes in the implementation, i.e., the live website.

- Requirements and changes in the implementation induce changes in the prototype.

You will usually observe a shift as soon as a prototype-based website goes online—at first, the prototype is authoritative, but changes after the launch will induce changes of the prototype. Make sure to avoid drift.

Continuity

Continuous maintenance, even after project finish.

Potential jackpot: The next relaunch is just a redesign.

Communication

Communicate changes, no matter if related to prototype or implementation.

…as implied by earlier requirements.

Documentation

Document design principles and characteristics (modules, constraints, snares).

This should be mandatory even though good, working prototypes rarely die of missing documentation.

Disadvantages

A good prototype requires:

- discipline.

Advantages

A good prototype means:

- easier and less error-prone development,

- easier testing,

- easier maintenance,

- better presentability.

…and thus:

- better quality,

- lower cost,

- more fun.

“More fun” through less frustration by fixing errors and bugs that have been caused by differing browser implementations. How many untested “sleeper” elements are there on your website?

Checklist

Is your prototype (and your design system):

- comprehensive?

- up-to-date?

- available, now?

About Me

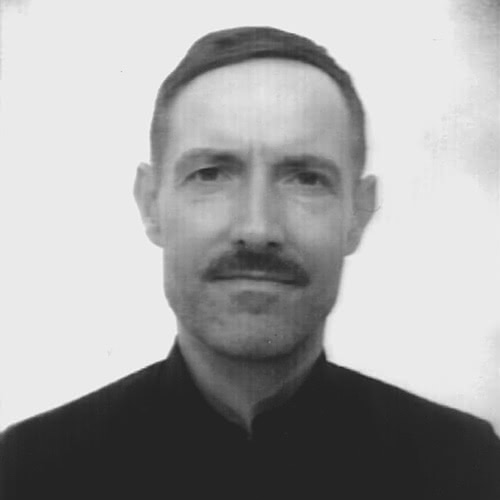

I’m Jens (long: Jens Oliver Meiert), and I’m a web developer, manager, and author. I’ve been working as a technical lead and engineering manager for companies you’ve never heard of and companies you use every day, I’m an occasional contributor to web standards (like HTML, CSS, WCAG), and I write and review books for O’Reilly and Frontend Dogma.

I love trying things, not only in web development and engineering management, but also in other areas like philosophy. Here on meiert.com I share some of my experiences and views. (I value you being critical, interpreting charitably, and giving feedback.)