70% Repetition in Style Sheets: Data on How We Fail at CSS Optimization

Published on May 31, 2017, filed under development, css, maintainability. (Share this post, e.g. on Mastodon or on Bluesky.)

This is one of 180 articles that you can also read in an ebook: On Web Development II. If the optimization of CSS is of particular import to you, I’ve collected several concepts also in another brief book: CSS Optimization Basics.

Teaser: Check on how many declarations you use in your style sheets, how many of those declarations are unique, and what that means.

Background. In 2008 I’ve argued that using declarations just once makes for a key method to DRY up our style sheets (this works because avoiding declaration repetition is usually more effective than avoiding selector repetition—declarations are often longer). I’ve later raised the suspicion that the demand for variables would have been more informed and civilized had we nailed style sheet optimization. What I haven’t done so far is gather data to show how big the problem really is. That’s what I’ve done in the last few weeks. (You can tell that the topic is dear to me.)

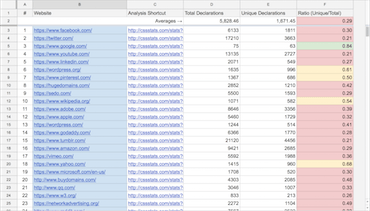

In a Google spreadsheet I’ve collected the Top 200 of content sites in the The Moz Top 500, and taken another 20 sites related to web development for comparison. (I’ve also added 3 of my sites out of curiosity.) I’ve then used the extremely useful CSS Stats to determine the total number of CSS declarations, as well as the number of unique declarations, to calculate ratios as well as averages: You get the idea as soon as you check out said spreadsheet.

A note on the sample: I removed those Moz top sites that were duplicates, one-pagers, redirectors, and placeholders (like international Google homepages, sedoparking.com, blogspot.com, youtu.be, goo.gl, bit.ly, &c. pp.), as well as those that derailed CSS Stats because of validation issues (of which there were so many, I stopped counting respective sites—validate! it’s part of our profession). I topped off using the next popular sites available, and given that I went as far as to include website #321 in the Moz list, you can see that quite a few sites were invalid either way. Although I’ve taken samples to verify that CSS Stats counts correctly, CSS validation issues might still distort the numbers (it did with Technorati, which I then removed); I accept this risk for workload reasons and the fact that lower declaration counts favor, not penalize, respective sites (less repetition reported than actually present).

A side note: About 37% of sites in the sample are still on http, including many commercial sites. (Compiling the list I believe that interestingly, none of the handful of popular Chinese sites have been on https.) Enabling https has become so easy, there’s not even an excuse for us with small sites not to switch, let alone for those who run some of the most frequented websites on the planet. Let’s encrypt.

Contents

Some Theory

Before we dissect the numbers, let’s first quickly establish what one can consider good CSS development practice:

As with all code, don’t repeat yourself (DRY).

In CSS, an effective way to not repeat yourself is to use declarations just once. The resulting repetition of selectors is less of a problem because declarations are usually longer than selectors—and yet variable selector length makes using declarations once a soft rule that still requires thinking. (We should also really think of selector groups here, as we only deal with selector repetition once all the selectors for a given rule are identical. That we repeat

h1in another rule forh1, h2is fine then, becauseh1andh1, h2are different selector groups—and hence they’re not a problem in terms of DRY CSS.)No repetition of declarations is theoretically attainable, but in practice, two things interfere: Not just in cases when selector order is mandated (another oft-forgotten subject, yet there are detailed proposals on how to standardize selector sorting), the cascade may not permit grouping of all selectors; and when strict separation of modules (CSS sections) is important, one may also tolerate some repetition. These two pieces deserve more elaboration, but relevant here is the note that strict separation of modules should not be used as a blanket refusal to curb declaration repetition—as the data show, that would be foolish.

Now, what is a reasonable amount of repetition? From my experience, 10–20%; in other words, 80–90% of a style sheet should consist of unique declarations. Reality, however, looks vastly different, and here we get to the 70%.

Some Numbers

The most important observation first: Per our 220 websites sample, the average number of declarations is 6,121; the average number of unique declarations is 1,698; and the average ratio of unique to total declarations 0.28 (median 0.34), meaning that 72% of the average style sheet’s declarations content is repetition (I rounded down in the post title). That is, per what we just established as feasible, 3.5–7 times more repetition than we really want (and need) to see.

Additional numbers and some interpretation before we talk more about DRY in CSS.

33 of the 220 websites use more than 10,000 declarations. Here the point we’re trying to make, that most websites repeat too many declarations, is particularly important: When we look at the data from this angle, no website tested and, given the high profile of the websites here, perhaps barely a website at all, should need more than a total of 5,000 declarations. The exceptions from the sample (the ones with the most unique declarations) rather prove the rule, and so this is an important observation as it may be able to provide a great red flag for teams working on large-scale sites.

The website with the most declarations, Kickstarter, uses 33,938 declarations; the next biggest website in terms of total declarations, Engadget, follows with 28,909 declarations. 8 more websites also use more than 20,000 declarations.

Kickstarter is not the website with the most unique declarations, however, though they come in second with 6,932 unique declarations; first here is Booking.com with 7,006 unique declarations. These high unique declaration counts probably help both not to become the sites with the most repetition (with ratio 0.2 and thus 80% repetition of declarations for Kickstarter, and 0.26/74% for Booking.com).

The most repetition we instead find on Engadget’s website, where only 2,382 of 28,909 declarations are unique (ratio 0.08/92%)—allow this to sink in—, meaning that quite possibly, more than 20,000 declarations could have been skipped. (Numbers like these should give us much to think.)

TED (0.09/91%), the Sydney Morning Herald (0.11/89%), Bloomberg (0.13/87%), the New Yorker (0.14/86%), the Guardian, and the Telegraph (both 0.15/85%) like to repeat themselves very much, too.

Very little repetition we find on my own websites (coderesponsibly.org, meiert.com, uitest.com), however I excluded those from the sample; Google.com should because of the site being so specialized, and thus code-wise rather small, be removed, too (they come in at 75 total/63 unique/0.84 ratio); that makes Yahoo be the first website of moderate complexity with relatively little repetition (1,406/952/0.68), followed by Wikimedia (261/167/0.64), Chris Heilmann (269/170/0.63), and, also more complex, WordPress.org (1,636/996/0.61). I believe that—entirely ignoring sites that I may have DRYed, which once included Blogger—Yahoo and WordPress.org provide very compelling cases for that DRY CSS works.

The 20 web development sites sample does fare better than the 200 Moz sites sample: 7 out of 20 attain a medium DRY score (>0.5, or less than 50% repetition), compared to 11 out of 200. The web dev sites are, on average, significantly less complex than the ones in the 200 Moz sample, but one may suspect, and hope, that web developers (on their own sites), write better, and more DRY, CSS. Personally I’m happy we see such difference for our own websites can be great showcases.

There are certainly more things to note; please review the spreadsheet and share your own observations.

Some Conclusion

The conclusion is the one you probably arrived at, too: In CSS, we repeat ourselves too much.

While it’s absolutely, practically possible to limit declaration repetition to 10–20%, reality averages 72% (median 66%).

That is bad news.

That is bad news, primarily, because this excess of repetition is the definition of bad code. CSS with this much repetition, this much bloat, is slow. CSS with this much repetition is also expensive: It’s expensive to create, and it’s particularly expensive to maintain (not even variables will save those who, on average, repeat each declaration nine times, like Engadget and TED).

That is bad news, secondarily, because it underscores how little attention we pay to optimize style sheets for production. It seems to indicate that some of our sources fail us, that they talk the wrong talk, or walk the wrong walk (this is something the “anti-pattern here, anti-pattern there” folk may actually want to look at). It seems to have lured us to prioritize differently what we most need in the CSS specs (cf., again, variables and constants that never had to be in the spec).

That, then, suggests at least two things we can do now:

Individually and collectively, let’s focus more on how to optimize, notably DRY, our style sheets. That most definitely includes all final production code. Don’t repeat yourself; look into using declarations just once, as long as you don’t begin to repeat selectors excessively (the rule has limitations; see notes).

Now if there’s one thing missing, something I‘ve only scratched in the original post on DRY CSS, is that using declarations just once means a different way of working with style sheets. I haven’t cared much about this here because this post is about what can make CSS DRY, not how the process is best done, but it’s something we’ll all notice when taking the points made to heart. I’m working on a follow-up post on how using declarations only once looks like in practice, offering a closer look at all the implications, and I encourage the community to explore the issue together.

One thing our analysis here prompts to look at, then, is how different exactly those style sheets are, and how much better they perform, that use 10–20% as opposed to 70% declaration repetition, because some of the improvements are lost with increased selector repetition. (The loss is often comparatively small, but not always, and so it deserves more scrutiny.)

Let‘s give more stage time to those who work on the really big sites and manage to achieve good code quality. The work of research coders has always looked glamorous and will continue to draw attention, but we can learn little from it when it comes to high quality production code. (Here is one real caveat we observe around DevRel teams. They are rarely the ones who keep their businesses’ infrastructure running.) High quality production code on complex, large-scale sites is more useful to base decisions on than much that just came out of a laboratory.

There’s much more to elaborate on and to qualify—the “answer” is somewhere in the middle—but I think that the basic ideas are clear. If you wish to look at other aspects of high quality web development, there are plenty more articles in the archives (regularly reviewed), and if you wish to read one of my brief books on web development, I believe that The Little Book of HTML/CSS Frameworks (updated) gives a great perspective on tailored web development and why if you want something excellent, your best bet, granted the expertise and resources, is to do it yourself; you, that includes your company and your team, for you, not the third parties, know best what you need.

Oh. Also, please sort declarations alphabetically.

Appendix

Example

I wish to not just point to my projects’ style sheets for how DRY works there, but also pick a rather complex case from the sample to perform post-optimization on that one. I selected Yandex (some time in April—the numbers changed a little since).

Here are files and data showing what I did, which was pretty much roughly formatting the style sheets and then DRYing them up (but not reviewing and optimizing them beyond that). The results are interesting for they illustrate a limitation of exclusive focus on declaration avoidance:

| File | Total declarations | Unique declarations | Ratio | Size (bytes) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yandex Original | 5,443 | 1,921 | 0.35 | 201,410 |

| Yandex Original, Formatted | 5,443 | 1,921 | 0.35 | 234,792 |

| Yandex Semi-DRY, Formatted | ? | 1,914 | ? | ? |

| Yandex DRY, Formatted | 2,083 | 1,914 | 0.92 | 237,033 |

| Yandex DRY | 2,083 | 1,914 | 0.92 | 220,513 |

Feel free to poke around and verify (and ponder what else you can tell looking at these and your own development styles); meanwhile, here are some things to note:

I wanted to demonstrate both moderate (“Semi-DRY”) and aggressive optimization (“DRY”) but had to go all in for aggressive optimization (for the ones who’ve never seen a declaration-DRY style sheet, that’s how they can turn out—with additional optimization, the style sheet wouldn’t nearly look as “scary”). The reason is actually trivial: I didn’t have access to the raw, likely structured and commented production files which would have made it easier to go for gentler module-based optimization (as opposed to the file-based optimization done) to show moderate editing.

That’s not a problem in terms of achieving maximum effect, however aggressive optimization made the style sheet actually larger (because of lengthy selectors being repeated “too often”—that’s the main reason why using declarations just once is not a hard rule), and more likely to lead to side-effects. So when you (or the Yandex team) are working with the optimized files, make sure to take the results with a grain of salt. Moderate optimization would have been easier to digest and easier to just plug in. When doing heuristic and aggressive post-optimization, turbulences are to be expected, and here we’re looking at somewhat of a paradigm shift for writing CSS.

Yandex, likely reflecting a modular instead of holistic development approach, ended up presenting a sub problem of the declaration repetition problem extensively discussed here: great repetition of media queries. The production files I had pulled included 56 media queries; these could be brought down to 36, which only then allowed to DRY up their contents.

Why fewer unique declarations? Because some optimization I couldn’t resist. If I see that there’s both

border: none;andborder: 0;(the latter to be preferred), then I consolidate declarations, like we all should.

FAQ

A few questions came up when asking for feedback on the first version of this article; as these touched on important points I’m feeling free to include them as a complement. I might add more Q&A depending on what additional feedback comes in.

Does this scale for larger sites, especially when styles are split across multiple files?

The larger the site the more repetition there’ll be, that looks like a fair statement to me. Yet this should be addressed by suggesting 10–20% repetition to be fine. On small sites, 0–5% may be attainable. As for whether the process actually works for large sites, yes, absolutely. The Yandex example above should serve as a proof of concept; as for separate files, one can at the very least aim to DRY respective sub style sheets.

What about mixins or other techniques which prefer repetition of declarations?

Mixins are a special issue because they are certainly convenient, but the very automation (compilation) that makes them so convenient stands in the way of avoiding repetition. It’s a problem I don’t have an answer ready for.

Does it still make sense from a maintenance perspective to avoid repetition when declarations are only coincidentally the same?

Yes, because with the idea of tailoring, everything that matters is the present. So when they’re the same, they should, ideally, not be duplicated. Also, in my mind there’s only the idea of practical, not coincidental, in a sense that if declarations are the same, one should aim to consolidate them.

How does e.g. moving a width declaration away from the height declaration affect maintainability and readability?

That can get a bit messy—so both could take a hit—but there are two things that soften the impact: 1) the freedom to limit avoiding repetition to sections (which is reflected by 10–20% “permissible” overall repetition) and 2) the observation that this is more of a restriction around general declarations, whereas specific page elements would be so unique to actually maintain bundling of their declarations. I’m inclined to add 3), that with this approach, one has a great opportunity to consolidate elements and class names, too, so that what at first seems to be inconvenient separation leads to welcome structural improvements elsewhere.

What about repetition because of vendor-specific extensions?

Vendor-specific extensions are relevant for style sheet management—extensions that aren’t needed anymore should regularly be removed—but not for the DRY keeping of CSS, because respective declarations are, de facto, different. -webkit-transition is not transition.

Why is Atomic CSS (or x) not being mentioned?

Why should it? (Please comment or email.) Atomic CSS, for instance, has not been mentioned because it’s not the solution to the different issues here. Perhaps it’s not even a solution: Atomic CSS style sheets do indeed appear to be more declaration-DRY than others, but not to an extent where we should be convinced that that’s all there is to say about DRY CSS, or about CSS optimization in general. This would stop the discussion right before it started, too. Furthermore, Atomic CSS violates some of the most fundamental principles for maintainability as well as for writing HTML; even though these principles reflect a traditional paradigm in web development, they represent a valid view at how to code websites that should likewise be addressed and handled properly.

_ The three main points of this long article summarized, then: We repeat ourselves too much in CSS; using declarations just once is often one solid avenue to avoid repetition; together, we need to put more focus on style sheet optimization. That focus is, indeed, most important: There are some tough problems in here for which I make suggestions, but we, plural, will still need to wrap our heads around them.

Thanks Tony Ruscoe and Kevin Khaw for reviewing and helping to improve this article.

About Me

I’m Jens (long: Jens Oliver Meiert), and I’m an engineering lead, guerrilla philosopher, and indie publisher. I’ve worked as a technical lead and engineering manager for companies you use every day (like Google) and companies you’ve never heard of, I’m an occasional contributor to web standards (like HTML, CSS, WCAG), and I write and review books for O’Reilly and Frontend Dogma.

I love trying things, not only in web development and engineering management, but also in philosophy. Here on meiert.com I share some of my experiences and perspectives. (I value you being critical, interpreting charitably, and giving feedback.)