On Semantics in HTML

Published on Oct 26, 2011 (updated Feb 5, 2024), filed under development, html, semantics. (Share this post, e.g. on Mastodon or on Bluesky.)

This and 133 other posts are also available as a well-behaved ebook: On Web Development.

As web developers we like to talk about “semantic markup,” a somehow inaccurate short form for “markup that is meaningful and used how it’s supposed to be used.” We also like discussions around what markup is appropriate when, and to ramble on markup that is “meaningless.” In many cases markup decisions and discussions don’t stop at HTML elements but also cover ID and class names.

Now when we’re talking about “semantic markup,” where is all that meaning actually coming from?

In essence, semantics in HTML is all about who and how many agree on the meaning, both of elements and ID and class names.

More thoughts.

In general you can say that initially, HTML and especially XML elements have no meaning.

In a way, however, we assign standards bodies like the W3C the authority (or accept their mandate) to tell us what HTML elements mean and what their purpose is. That is, only through these bodies’ directive do we agree on

pelements representing paragraphs,ulandolelements representing lists, and alsodivelements carrying little semantic weight.It would well be possible to both not assign these elements any meaning (that’s what authors involuntarily did with using tables for layout), or to assign them a different meaning (why would

pnot be great for parentheses?).Similarly, we accept certain communities’ interpretation of what markup may mean. Think microformats. Their markup constructs don’t have any meaning, either, per se, but with a lot of people agreeing on their purpose they do become meaningful.

Next in line is common sense. A class like “error” or an ID “author” has meaning because it defines a purpose that can be understood and also agreed on. With these names also being advisable for maintainability reasons we now know why functional ID and class names are most useful.

Then the terrain gets a bit more rough with generic names like “aux” or “alt[ernative]”. Here we’re leaving the semantics trail as generic names are harder to grasp, yet their purpose is less to add meaning but to avoid pseudo-meaning and serve as helper constructs.

Last are obfuscated, random, or presentational names. They are meaningless and should be avoided. Presentational names especially as they impose the biggest threat to maintainability.

As this list goes from “most meaning” to “least meaning,” you can see why blockquote can rather be accepted to mean a quote than “vcard” for an hCard container than “login” for a sign-in field than “aux” for a helper class than “red” for I don’t know. It also shows why you don’t need to have a class “list-item” on an li element as it is already defined as a list item on a higher, namely the spec level.

As I love disclaimers, this may not be all there is to say about the topic but it was good enough for a write-down-everything-that-comes-to-mind-on-semantics-now post.

Update (August 5, 2014)

In the meantime, in 2012, I also wrote an article about semantics for Google. I believe it adds detail and value to the points made here.

Update (November 3, 2014)

Web Components and custom elements rank the same as IDs or class names in terms of meaning, and the same naming best practices apply.

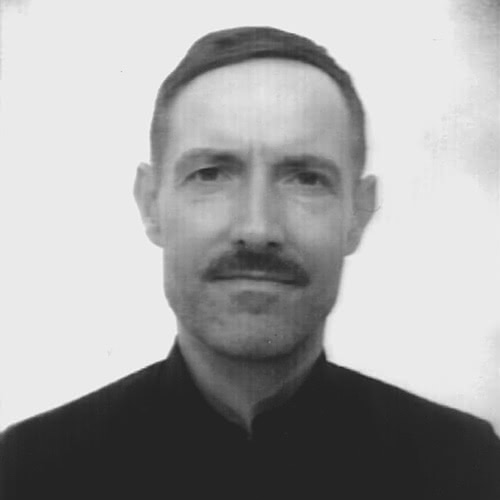

About Me

I’m Jens (long: Jens Oliver Meiert), and I’m a senior engineering lead, guerrilla philosopher, and indie publisher. I’ve worked as a technical lead and engineering manager for companies you use every day and companies you’ve never heard of, I’m an occasional contributor to web standards (like HTML, CSS, WCAG), and I write and review books for O’Reilly and Frontend Dogma.

I love trying things, not only in web development and engineering management, but also in philosophy. Here on meiert.com I share some of my experiences and perspectives. (I value you being critical, interpreting charitably, and giving feedback.)